As we arrive at the mid-point of November, one can hardly avoid thinking about this curious bit of business we call, the moustache. Everywhere we look, there are men with varying degrees of stubble. On the commuter train or bus, in the grocery store, at the office or plant. At every turn, we’re likely to see a self-conscious lug, quelling the itch, assessing progress between forefinger and thumb, or trying to catch a quick glimpse of their work as they pass shop windows. A Mo Bro is not overly difficult to pick out in a crowd.

Since its introduction in 2004, Movember has been a growing phenomenon, designed to spread awareness of mens’ health issues. The full month of November is dedicated to men growing moustaches. It’s a playful initiative with a serious objective to “change the face of mens’ health” through early detection, diagnosis, and effective treatment of prostate cancer, testicular cancer, and mental health issues. The program is widely recognized and practiced in countries throughout the world. It seems the combination of a very worthy cause and the relative novelty of the moustache, in this era, have aligned nicely.

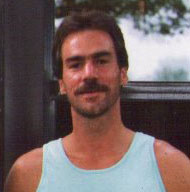

It’s a program that may not have taken root 30 years ago. The moustache was not always the grooming anomaly it is today. In the 70’s and 80’s, a dressed upper lip was a veritable fashion fixture among men. It was almost a rite of passage to cultivate a puerile offering as a young lad came of age. If you were to dig up and dust off the family photo albums of the era, you’d be hard-pressed to find a male, north of puberty, that wasn’t sporting some variation of moustache.

There was no shortage of role models in the day. ‘Staches of all varieties were worn by television, movie, and sports celebrities. Burt Reynolds, Tom Selleck, Sonny Bono, Frank Zappa, and Lanny McDonald, to name a few, boasted top-of-the-line nostril-ticklers. A lush, well-coiffed moustache was a thing of beauty. Adored by many women and the envy of whisker-challenged men.

**************************************************

Somewhere along the way, all that changed. A new generation of youth began to inexplicably associate the once majestic lip-jacket with persons unsavory. A sighting of a Borat-quality ‘stache was ridiculed, rather than regaled. Women, once staunch proponents of a shaggy upper lip – with some exuberant exceptions – now seemed bemused, or indifferent.

From a societal point of view, it was likely the combination of the unflattering connotation by the younger generation, and its loss of appeal for many women – a not insignificant motivator of men – that dealt the ‘stache a blow that drove would-be wearers into submission. Gillette and Shick product sales flourished as men begrudgingly adopted a regimen of daily shaves. And in the doing, flushed the bristles of former glory – and a long tradition – down the drain.

But the allure of growing facial hair is never far from the surface for men. There is a certain machismo at play for the male of our species. A primal need to showcase our virility. A testosterone driven validation of our manhood. A hunger to feed that competitive spirit. It seems we are instinctively inclined to be bigger, stronger, and faster than the next guy. A dispute is as likely to be settled with an arm wrestle as a coin toss. Growing facial hair quicker, longer, and thicker, is simply another way to demonstrate relative masculinity. As a chest-pounding differentiator, it ranks right up there with the size of our – feet.

**************************************************

It seems there is also – at least anecdotal – evidence of a compensatory component to facial foliage tied to the delicate egos of men. For example, one of modest height may be more apt to assert himself with a hearty beard or moustache. And in a twist of irony, some of the best displays of facial hair are liable to be found on the mugs of balding men. While beards and moustaches are not as prevalent as they were a few decades ago, they are by no means extinct. These days, there is something of a resurgence in the form of the ‘close-crop’. While fashionable, these are more shadow-like – or silhouettes of the real thing. Short of religious convention and playoff beards, odds may be better these days, to find facial hair on a short, balding guy.

The increasing popularity of Movember has given new life – and a window of social acceptance – to the art of moustache growing. We get a period of immunity from our children, or at least, more subdued references of derision. Men are granted – from wives, girlfriends, partners – a free pass for a month of bristles. Employers tolerate the scruffy look, for a good cause. The ‘boys’ get to compete with friends and colleagues for moustache supremacy. And, the middle-aged among us have an opportunity to assess the encroachment of gray, each passing year.

At a business conference I attended in late November, a couple of years ago, the group was given ballots to vote for “winners” under a variety of categories. Among the dozen or so Mo Bro participants, I proudly accepted the award for “Moustache Most Likely to Collect Crumbs”. While I secretly had mental images of looking a little like, well, Magnum P.I., there was a sufficient number of comments suggesting I had achieved much more of a likeness to Sam Elliott. We take what we can get.

********************************************

As we push through the next two weeks and close out the month of November, participants will pause to enjoy the camaraderie and good-natured ribbing that’s sure to ensue. It’s always a month of fun. There will be a sense of satisfaction and accomplishment for participants, for raising awareness and funds in a very good cause.

For most Mo Bros, the charitable ‘staches will be unceremoniously lopped come the end of November, to restore a clean-shaven identity. This, in the end, is probably good for the cause. It will maintain the very novelty status of the moustache, that makes Movember work.

And come the cool breezes on bare faces of well-intentioned men, next November, it will all start over again.

************************************************